On Photographing Punk Musicians – Part 2

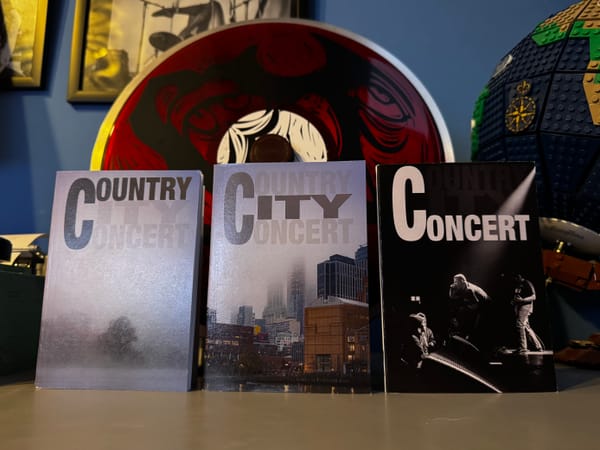

Recently I published my latest zine, How To Photograph Punk Musicians In 5 Easy Steps. This newsletter contains a chapter of that zine, with more to follow. If you like it, please consider buying a physical copy at store.terror.management.

I also have copies left of my earlier zine, Terror Management, containing edited versions of essays previously published through this newsletter. Foreword by Greg Bennick (Trial, Between Earth and Sky, Bystander). Thank you.

Chapter 2: Free Yourself From Worldly Concerns

With enough time, one could argue that nearly anything is an illusion. But for this chapter let’s limit ourselves to our physical safety during a punk show. At any point in time, at any location, for any given reason (or none at all), you might get hurt.

So what do you think might happen if you take an expensive camera into a public arena where concepts such as ‘crowd killing’, ‘spin kicks’ and ‘head walking’ not only exist, but dominate the space that you yearn to occupy? That’s right: your camera will get fucked up, one way or another.

(Don’t mistake this for me saying it’s acceptable to destroy someone’s camera. Just that it happens.)

There are ways to mitigate this, naturally. One way would be to simply not stand near the stage. Perhaps, if the physical attributes of the venue allow it, one could stand further away and use a zoom lens to take pictures.

This notion I reject fully.

Do not be mistaken: the begotten pictures could be mindblowingly beautiful. However, if they were not taken in a situation where at any point you could get spin-kicked in the head or could have someone jump on top of you, are they really photos representative of the spirit of a show?

This is a joke. But also. This is serious.

From top right to center, clockwise: Dead Heat, 2022 / Altar, 2018 / Touché Amoré, 2023 / Magnitude, 2022 / Catharsis, 2023 / Wolfbrigade, 2019 / Skroetbalg, 2023 / Discharge, 2019 / Suffering Quota, 2019

In trying to capture the moment in a still image, the circumstances of image capture are just as, if not more important than subject matter, the composition or other technical details. As noted in chapter one: despite the popular misconception that a photograph is a close approximation of reality, it actually has very little to do with it. Instead, it’s the photographer’s choices and situation that make the photo, truly.

And so it is that if you as a photographer decide to stay well away from the mess of bodies in front of the stage, this is not a truth you will adequately capture.

Standing far away and using a zoom lens makes it so the subject matter becomes the most important thing about any photo you take this way. You have become an observer, a wildlife photographer. Standing in front of the stage with a wide lens, possibly afraid for your equipment or even life, you are part of the culture. This has the possibility to elevate your work.

Again: this is serious.

To be fair, I am by no means advocating putting yourself in harm’s way purposefully – that’s not the point of the above. Also, I fully acknowledge the privilege of being a pretty chunky man that can take a knock – not everyone can.

The point is that in punk, participation is a crucial part of the entire experience. It is – in this humble photographer’s opinion – the thing that sets this genre and its many adjacent forms of music apart from any other.

What other type of concert allows audience members to get up on stage, jump off of the highest point in the venue on top of other people, dance violently into the night and still allow you in the room? Try that shit at a Taylor Swift concert and see how you fare.

And if you’re there to capture something about this concept on camera, don’t hide. Make your photography part of the moment. Make the photos you take count. Make anyone that looks at them feel like this is an experience worth having.

This state is unattainable if you’re constantly worried about your gear. Sure, no one likes having their shit getting fucked up, but it’s the risk you have to take.