Issue 8: 108 – Songs of Separation

Seething grief

On loss.

Part I: An empty shell

A husk was laying before me. An unconscious man on a hospital bed, gasping for air. My father warned me before coming here, telling me: “He’s in a bad way, he’s not what you remember him to be. I want you to remember him like he was.” A warning I ignored, insisting on seeing my grandfather one last time.

At barely twenty years old, standing in the dark blue shades of the hospital room, I experienced a harrowing sight: a man still attached to his soul only by the barest of threads. Not knowing the right thing to do – desperately wanting to pull him back to this plane, but lacking the ways to do so – I saw him, I hugged him, and I left. At times I wonder if he even knew I was there.

“That thing that screamed with me

And dreamed with me."

During the night that followed, the thread was severed. After a short sickbed, my mother’s father was no longer alive. It was the first time I lost someone so close to me at an age where I could mentally process it, my other grandfather having passed away when I was so little it left no active memory. A macabre debut, a shock to the system, but as with most of these impactful moments, something to learn from, a chance to grow.

In our western culture, corpses are generally seen to be things to be scared of, to stay away from. Perhaps diseases associated with them taught us as a society that lesson centuries ago, perhaps it’s because they symbolise the end of this life – a truly terrifying thought. But standing in a small, grey side room of the crematorium where my grandfather’s body was about to be turned into ash, his body didn’t phase me much.

"That thing that laughed with me

And cried with me."

There was hurt, of course. But the hurt I was feeling, was caused by missing the person I spent countless hours with running around his farm, riding on his tractor and helping him feed the animals he kept. That man was not there with me at that moment. What lay there, in the casket, was a vessel which had now been abandoned and was slowly decaying, be it not for the chemicals used to preserve it.

I still cried when the service was nearing the end. But it wasn’t for the body, or the loss of it. It wasn’t even because I missed him already. It was because there is no clearer reminder of mortality and what it entails than witnessing the end of a life, the finality of it all. He was not coming back to me in this realm ever again. The final bang of the gavel by the cosmic judge who will one day sentence us all.

"That same thing lies before me

On this deathbed

But where are you?”

Over the years, that memory has become inextricably linked to 108’s song Deathbed. A song with a theme that is, I’m sure, universally recognisable.

Weirdly enough, for a song that made such an impression on me, I’m not quite sure how or where I first encountered it.

Music discovery in the late ’90’s and early ’00’s mostly relied on filesharing services. You liked Shelter? Chances are the person you downloaded that from also had a folder called '108' somewhere on their computer that you could dip into. Many random tracks from bands found their way into my life through this digital portal, including, in my estimation, 108.

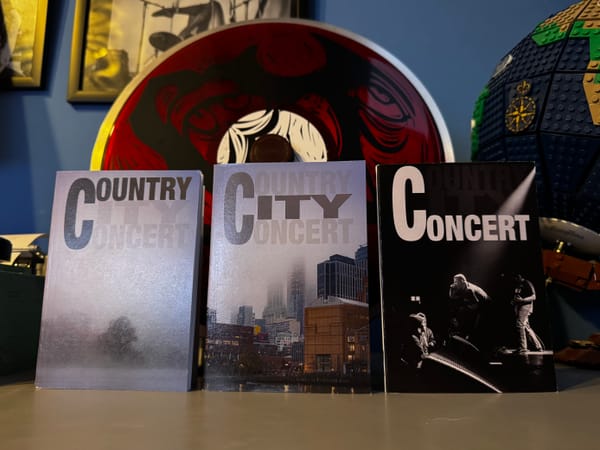

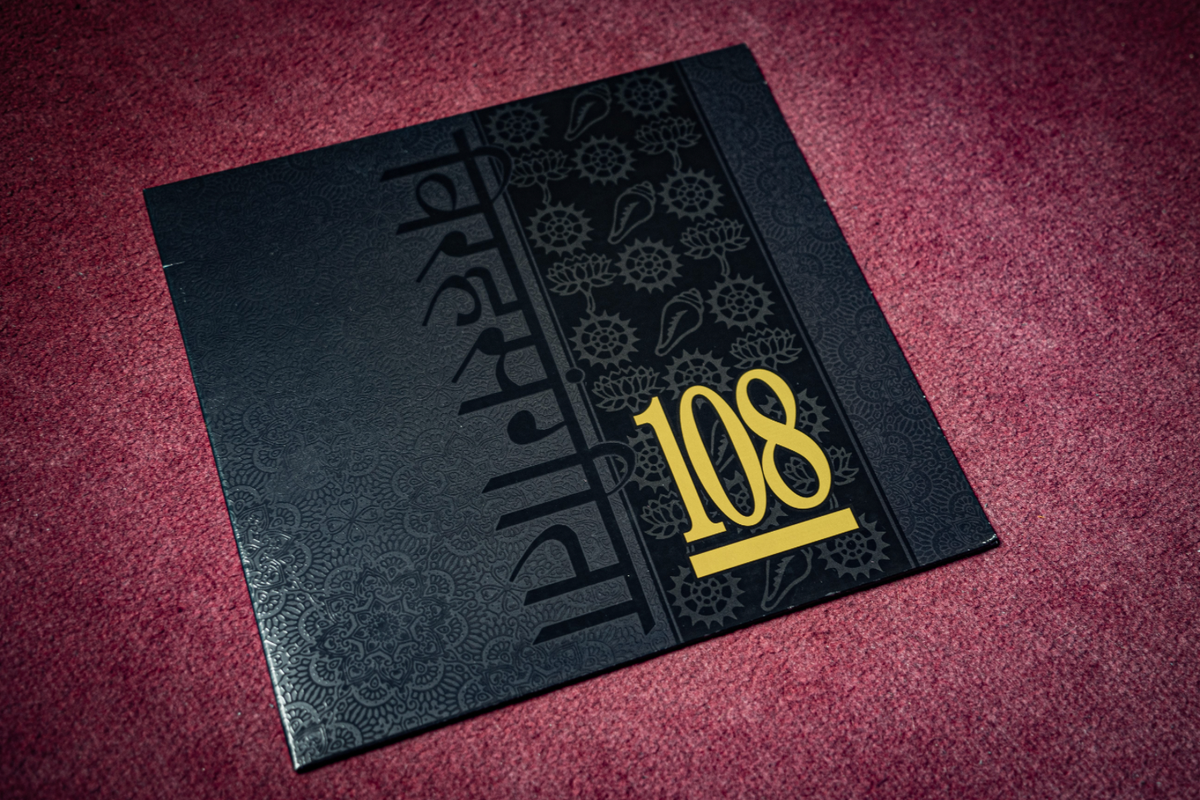

Although I know it’s after my grandfather’s passing, I’m not entirely sure when and where I bought the (then) full 108 discography Creation. Sustenance. Destruction., but I still have it. It’s a weird misprint, where all 36 songs were merged together as one track on the physical CD. No skipping around here.

When it reached Deathbed, originally released on Songs of Separation, a wave of emotions washed over me. “Your body’s here,” singer Rob Fish speaks during the bridge, “but you’re not.” Once more, he says it, more forcefully. Then again. And again, each time taking the intensity up a notch, infusing the lines with a bittersweet emotion all too familiar to me.

Part II: Heavy metal Hare Krishna

In the pursuit of approachability and a friendliness in the face of a hardened western monotheistic society, Krishna Consciousness from the beginning has tried to brand itself as the religion of those cheerful bald fellas who walk down the shopping street, cheerfully singing and dancing in their cheerful orange robes, all the while distributing cheerful literature.

Much like with Christian evangelism that puts up a friendly face but hides a gruesome collection of stories in the bible, it’s not until one dips their toes in the theistic waters that you’d read the stories about beings such as Nrsimhadeva, the half-man, half-lion incarnation of Krishna that is mostly depicted as having a man in his lap that He is at that moment actively disemboweling.

Such was also the jump from listening to a band like Shelter to listening to a band like 108. Make no mistake: Shelter was not shy in preaching austerity and raging against Western societal norms, but it nevertheless did not fail to put on a somewhat cheerful front, with a more accessible post-hardcore and later pop-punk musical set dressing to make the medicine go down.

108 channeled all their aggression into their music, and broke clean away from the happy-clappy-jingly-jangly Hare Krishna’s down Main Street with a more metal-inspired sound. However, despite the aggressive music, the band contrasted the mostly macho attitude that most hardcore punk bands were putting out into the world at that time. The songs of 108 invited self-reflection and humility. The band still trafficked in a revolutionary message, however, with songs like Killer of the Soul laying clear judgment on the eating of dead animals (among other things) and Scandal taking aim at the deliberate creation and spread of misinformation about the devotee way of life.

An important part of why the band spoke to me, was that the whole enterprise never seemed to take the evangelism part of their religion all that seriously. Or at least, if they did, they went about it in a strange way. Forsaking accessibility, the lyrics not only are more esoteric and open to interpretation than those of most genre-mates, they also heavily reference figures from lore, mantras and other phrases that required more than a passing knowledge of the subject matter to be able to interpret.

And I loved it.

As a nerdy kid with a penchant for deep-diving into fantasy and sci-fi lore, this scratched my spiritual itch in a very particular way. Combined with the aggressive music that soothed the seething manchild inside of me, 108 had everything it needed to sink its hooks into me.

The band quickly surpassed Shelter as my go-to form of religious engagement. Lacking a temple so nearby that I could regularly visit, the music did its part to connect me to my newly chosen spiritual path. Solitary’s “Each moment without you I die, o Krishna” became a chant unto itself, supplementing the mantra’s and kirtans that my newly found religion already supplied.

And then there is Deathbed. The music taking a different tack, with a slow build to a big emotional explosion rather than a full-on assault of the senses from the start. What grabbed me more than anything, however, were the lyrics, which worded a feeling I had but could not quite manifest into language. It’s one of those songs that you immediately accept wholly, like it slots into your brain like a puzzle piece.

Part III: Scar tissue

As one of the few constants in life, death keeps rearing its head. As the years tick on, the more frequent the occurrence in one’s periphery. Pets, grandparents, uncles, aunts, parents, sometimes friends or even children – they all pass and there’s not a single soul that will not have to deal with grief at one point or another.

My grandfather was the first one in my life whose passing left a big impression, the one that taught me about grief, and to grieve. Through these harsh ways, I learned that grief is a scar that never leaves you, merely fades slowly with the years. In the beginning it’s fresh and sore and stands out on the skin and underneath your touch.

As time passes, it becomes less visible and you notice it less, though sometimes the old wound will act up and you can feel it. It also becomes a part of your essence, a thing to remind you of a specific event that, while painful, might also bring back good memories. The scars we gain over the years shape us, from the small nicks we take on the chin to the big wounds that incapacitate us and leave us needing help to move on from.

Music helps, certainly. It soothes, it comfort us. It also helps us put emotions into words and realise that our experiences are somewhat universal, even when it comes to processes that are steeped in pain and shame. A moment of weakness shared becomes a step forward.