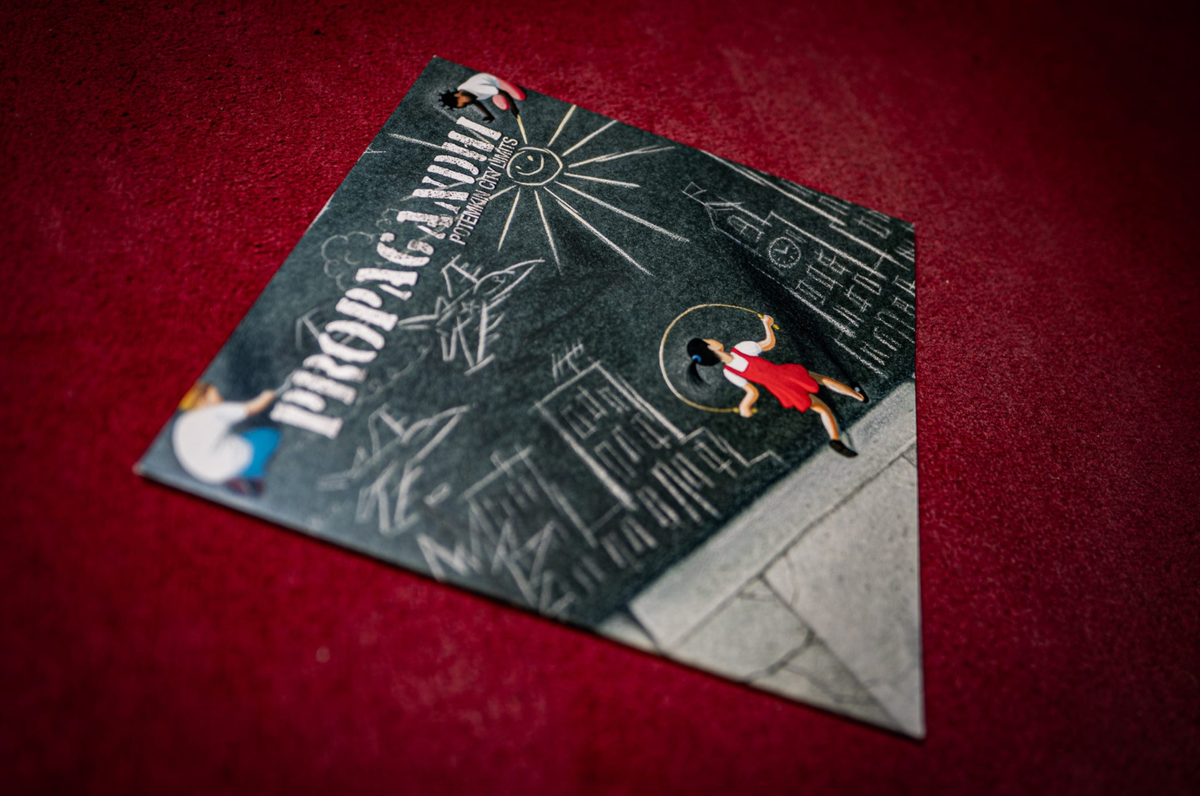

Issue 13: Propagandhi – Potemkin City Limits

A little naivety goes a long way

On money and music

Part I: Pay me, daddy

Life would not be worth living without art, in all its beautiful, dumb facets – this much I know. Its ability to communicate that which cannot be put into direct words is what can elevate an otherwise mundane and straightforward march into oblivion.

More than any other form of artistic expression, music has the firmest hold on my heart. Nearly indistinguishable from magic, the way sounds can dig into the spectrum of human emotions and either slowly coax a very specific feeling out of us or build up a storm of them only to break the dam and have it all pour out at once.

And of course we continuously manage to ruin it in the saddest way and over the most pathetic reason possible: money.

No, not a tirade against "selling out!" Despite my misgivings about capitalism in the broad sense of the word (and basically every specific sense of the word too, while we’re at it), I also fully realise that people, and that sometimes includes musicians, in fact like to be able to eat and be housed. Regrettably, in the current state of the world those things require income.

And yet. And yet…

Listen, I’m not going to touch on the mainstream music industry – it’s gross, and the less said about it, the better. It’s also hard to talk about – almost any artist will take the opportunity to do what they love and get paid for it enough to be able to dedicate themselves to their passion full-time. Far be it from me to cast any aspersions on them. Of course it doesn’t help the toxicity trickles down from the top where the bottom line is more important than actually putting out good music, but hey.

Set against this scenario, that’s why I respect the extreme niches more: you don’t dedicate your life to this type of music, whether as a musician, running a label or as a promoter of shows, thinking you’ll get rich. As someone who’s been in a metal band and has organised hardcore shows – buddy, these things only cost money. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a powerviolence band to become filthy rich. There is a love for the art in these niches.

And yet, as we see time and again, the underground doesn’t always stay under ground. How many times have we seen punk be coopted by capitalist forces? It’s always an empowering time when you see your pop punk friends hawking a phone with a built-in Facebook share button or when one of the most recognisable punk songs in history is used to sell Pepsi.

(Ah yes, PepsiCo, truly your friend for the revolution)

This is gross, right? I’m not the only here that sees a genre of music that’s built on DIY ethics and anti-establishment messaging being dragged through some shit for a few bucks? I can hear the chorus of "naive little boy, learn how the real world works" swelling. And yet, over the 20+ years that I’ve cared about punk rock, I’ve never been able to shake this way of thinking.

And so, let me make an impassioned plea for the naivety that says that music is at its best when money stays as far away as possible from it.

Part II: Intent on intent

This whole train of thought brought to you by track #7 on Propagandhi’s Potemkin City Limits, the band’s fourth full-length album.

Propagandhi of course being the band that’ll make you google fucked up political situations so you can go "ok, that’s actually a good joke."

A slight detour from their usually more worldly politics-infused fare, Rock For Sustainable Capitalism kicks off as a searing indictment of punk rock’s millionaires and label bosses, followed by corporate punk tours and the urge to make gross deals.

Music’s power to describe, compel, renew

It’s all a distant second to the offers you can’t refuse.

Written and delivered with passion, the song isn’t so much about bands "selling out" as it is about what an intrusive and subversive influence money can be, not to mention that it spawns the boring sonic wallpaper we call corporate rock.

As fun as that first half of the song is – and there are very few bands out there with lyrics that are as sharply polished as Propagandhi’s, as seen here – it’s the second half that recently bored itself into my brain.

Anyone remember when we used to believe

that music was a sacred place and not some fucking bank machine?

Not something you just bought and sold?

How could we have been so naïve?

Hearing these lines shook the cobwebs from my brain, not having thought about this in a long time. And yet, it’s a value that’s so deeply ingrained in me that I will never be able to escape it: if your art merely exists for the sake of money, it’s not real. Whether it’s music, visual or written: intent has to come first.

An ad can only be the shittiest possible form of art: the deceitful kind. It might elicit an emotional response, but it is fundamentally always ready to pull the rug right out from under you: "Oh you made me cry with this beautiful story of a woman emotionally reconnecting with her grandfather… Oh wait you want me to buy a Ford."

And so it goes with music as well. They who give their audience the feeling that they are merely walking cash machines, simply cannot penetrate the heart. Give me an artist who commits:

And I’ll rock back and forth on this two-bit hobbyhorse

’til she splinters and gives way.

I’ll tend the flowers by her grave.

And whisper her name.

Part III: Moneyvator

They say intent does not matter if the end result of your work does not resonate with the audience. So let me be explicit here and tell a short story about why Terror Management exists:

In my day job, while it is a creative profession to a certain extent, I do not get to express myself fully in the work that I do. Which is actually probably for the best, as who would want to put their own artistic essence fully in the hands on their corporate overlords? Sounds terrifying.

And so a creative yearning inside of me went unfulfilled until I figured I should just stop whining about it and do something about it. The internet is free, after all1, and so I started writing about my big love: music.

But I’ve learned one thing from previous jobs: never turn your passions into money-making endeavours if you can help it. As expounded upon above, money is not a great motivator for making healthy artistic decisions, and so I decided to consciously keep This Whole Endeavour a hobby, and therefore on my own terms in every single meaning of that phrase.

And let’s not kid ourselves here: I’m not going to make money pontificating on old records that only a handful of people (relatively speaking) have ever heard of anyway. So let’s keep it that way. And in turn, I can set my own publication schedule, ensuring I only have to write and publish when I feel I have something to contribute and not because I have to be worried about subscriber or visitor numbers and declining ad income, leading to bad opinions designed to maximise engagement.

It also means that I know the handful of readers that this publication has, actually cares. You’re not here because I made you mad with a misleading clickbait headline on Twitter or a shitty TikTok. Quality over quantity, also in readership. This heartens me.

And so, I will rock back on forth on this two-bit hobbyhorse of my own, until it, or I, comes apart.

I mean obviously not, but you know what I mean. ↩